A Consumer-Relevant Approach to Assessing Absorbent Hygiene Materials for Trace Chemicals

Manufacturers of absorbent hygiene products (AHP), such as baby and adult incontinence disposable diapers or inserts, feminine pads, or liners, have robust safety programs in place to ensure the safety of their products for consumers who use them. One aspect of this is a detailed understanding of the chemical composition of both raw materials and finished products. With this knowledge in hand, we can perform a toxicological exposure-based risk assessment (EBRA) to ensure that any risk associated with the possible presence of undesired impurities or environmental contaminants is insignificant.1,2,3 In the course of EBRA, a toxicologist may request that the total content of a given trace chemical in a product or product component be established, and in response to this need, an analytical chemical analysis may be performed. Additionally, targeted experiments assessing exposure factors such as rewet may be performed to optionally further refine an EBRA.4 Numerous other factors (skin exposure, skin penetration, hours of product wear, products per day, days or use per month, year of use in a lifetime) are customarily part of the calculus to arrive at a (often conservative) exposure estimate, which that can then be compared with known exposure limits to assess risk. In this way, EBRA represents the most consumer-relevant means known of assessing risk.

The Growing Focus on AHPs

While the EBRA approach is recognized from a toxicological standpoint as the gold standard for assessing the acceptability of consumer risk associated with a potential chemical hazard, it is a complex analysis that is often absent from the evolving discourse about the presence of trace chemicals in AHP. The landscape associated with concerns about potential trace chemicals possibly present in AHPs is ever-changing, and simultaneously becoming a greater area of societal focus. More regulatory bodies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), consumer associations, and even academic researchers are expressing concern about trace chemicals. In many cases, in response to these concerns, these same stakeholders are commissioning laboratory work in which AHP articles are being extracted and trace analytical measurements are being performed to suggest potential exposure risk.

Much of this measurement work is spread across individual laboratories which apply laboratory-specific methods and sample preparation conventions. Individual laboratories, in response to measurement requests from customers, typically adapt methods developed initially for trace chemicals in environmental (e.g., soil and water) or medical (e.g., blood serum) samples. Moreover, laboratories often pursue sample preparation using what might be considered “harsh organic solvent extraction” with the goal of establishing the total content of a trace chemical present in an AHP article. In the case of elemental analysis (metals and metalloids), an analogous harsh approach oriented toward content is microwave-assisted acid digestion.

While such harsh analysis may be appropriate within the context of a sophisticated EBRA, harsh-organic extractions themselves are not oriented toward or representative of true potential consumer exposure. And because a full EBRA analysis is generally absent from these studies, a gap exists between what is often reported (harsh-organic extractions, perhaps more indicative of “hazard”) and what a consumer might be exposed to – that is, toxicological risk. However, this gap is often lost in discussion among stakeholders or the popular media, leading to unwarranted concern and fear among consumers. One step in the right direction is for stakeholders to use more consumer-relevant analytical methods that are more closely related to an (conservative) estimation of consumer, and for AHP manufacturers to similarly use a more consumer-relevant method when interacting with regulators, retailers, consumer groups, and NGOs, where a complete EBRA discussion is generally not an option.

As part of its Stewardship Programme for AHP5, EDANA6 developed standard method NWSP 360 that makes a significant step toward bridging the above mentioned gap. In short, to considerably enhance the inherent consumer relevance of a method result, a biologically relevant fluid simulant (either urine or menstrual fluid) is used in the extraction of finished product AHP. Subsequently a CEN Workshop was convened that resulted in a closely related method CEN Workshop Agreement CEN CWA 18062 “Determination of trace chemicals extracted from absorbent hygiene products (AHPs) using simulated urine/menstrual fluid,” hereinafter referred to simply as “CWA 18062.”

The Dynamics of CWA 18062

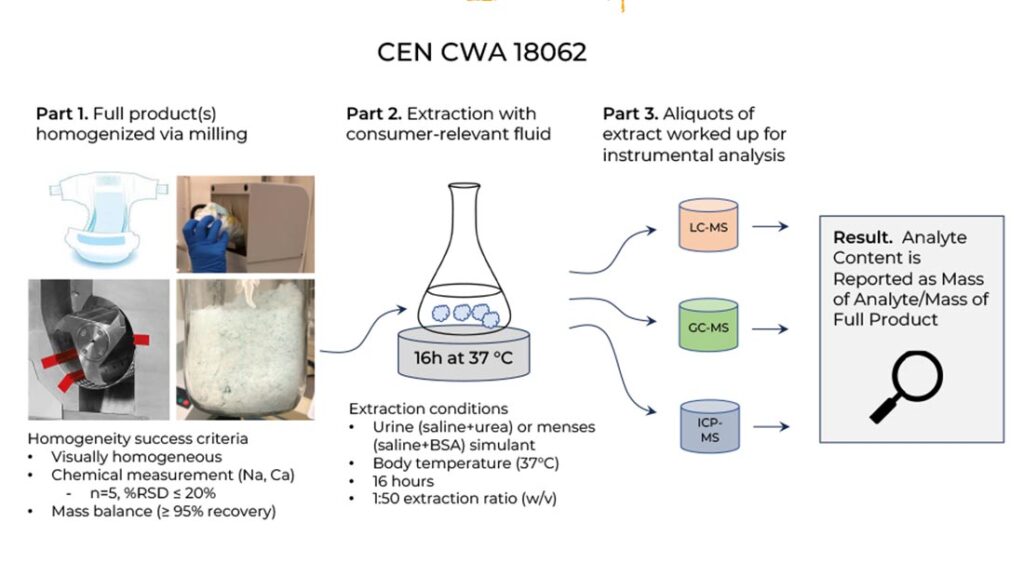

CWA 18062 consists of three distinct parts, as illustrated in the Figure 1. In the first part, the full-finished AHP as used is homogenized via milling. In a second part, this homogenized material is extracted using a consumer-relevant body fluid simulant. The simulant for urine is 0.9% physiological saline with 0.93% urea added, while the simulant for menstrual fluid is 0.9% physiological saline with 1.0% bovine serum albumin added. Finally, in the third part, the body simulant is worked up and analyzed using one or more analytical instrumental techniques appropriate for the trace chemical(s) being investigated. The method provides specific guidance for the performance of true method blanks and the appropriate relationship between method blanks and reporting limits, which is critical in developing reliable results, particularly when dealing with trace chemicals widespread in the environment that may be present at low levels in a laboratory. Final results are reported in mass of trace chemical (if detected) per mass of finished AHP.

We note that the contrast between the harsh-organic extraction method and the use of consumer-relevant, biorelevant fluids approximately parallels the well-established concepts of extractables and leachables, respectively, which are widely accepted in drug- and medical-device-oriented biocompatibility testing. For example, see ISO 10993 (particularly parts 1 and 18) as well as US FDA guidance on the same.7 A bio-relevant approach, as outlined in CWA 18062, is analogous to leachables testing according to ISO 10993, where the goal is to determine what could potentially be released from the tested item during actual (clinical) use. During the development of the closely related method NWSP 360, EDANA assessed a range of urine simulant and menstrual fluid simulant compositions based on the principle that if a simulant ingredient present in real urine or menstrual fluid gave rise to a higher recovery of trace chemicals, it should be included. One example is the inclusion of 1% bovine serum albumin in the menstrual fluid simulant. Menstrual fluid contains albumin proteins, and it was found that the presence of albumin proteins in the simulant increased trace chemical recovery, particularly among more hydrophobic analyte classes.

CWA 18062 aims to strike a balance between the needs of relevance, robustness, and deployability in a manner that is beneficial to a wide range of stakeholders in the AHP industry and regulatory landscape. Relevance refers to the extent to which a method directly mimics a consumer’s wearing experience. Robustness refers to the ability of a method to be performed reliably by a range of laboratories and personnel with minimal possibility of small perturbations in procedure giving rise to large, unexpected perturbations in reported results. This quality is particularly important in the context of trace chemicals, where reported levels are often not significantly above those in the environment, in laboratories, and even in high-purity laboratory reagents. Finally, deployability refers to a method’s ability to be performed in its entirety by a wide range of laboratories worldwide in both a cost-effective and timely manner.

Setting Optimal Expectations

A mutual tension generally exists between the three goals of robustness, relevance, and deployability. By optimizing a method for one or two goals, the other(s) are often suboptimal. For example, a harsh organic extraction of a sample is generally fairly robust and can be performed in some form broadly, but it departs markedly from the wearer’s experience. One challenge in creating a more consumer-relevant method is that the level of consumer relevance often competes with its robustness and broad deployability for routine execution.

Two aspects of the method paradigm followed by CWA 18062 illustrate this tension. First, the use of consumer-relevant, bio-relevant fluids is a key component of the method. However, these fluids have been simplified from “real” fluids, making them more robust and deployable. They have been simplified as much as possible – but no further! These fluids maintain critical chemical aspects to be consumer-relevant. Second, the choice of a method paradigm, including whole-product homogenization, departs from literal consumer use relevance but carries with it numerous benefits in method robustness and deployability that more manually intensive, rewet-based extraction methodologies, for example, lack.

A mutual tension generally exists between the three goals of robustness, relevance, and deployability. By optimizing a method for one or two goals, the other(s) are often suboptimal.

Since the use of homogenization intuitively departs from the most consumer-relevant approach, further discussion of the specific approach to sample milling is warranted. AHP articles are milled to create a finely divided, homogenized sample for subsequent extraction and analytical instrumental analysis. Typically, a minimum of two articles is used to generate a sufficient homogenized sample for further work.

Milling is performed on dry (equilibrated to laboratory conditions) AHPs using a capable mill, such as a Retsch SM300. AHP articles are milled whole such that surfaces and materials that touch the skin during use are not distinguished from surfaces that do not touch the skin. Similarly, surfaces and materials that may be wetted during use are not distinguished from surfaces that are unlikely to be wetted during use. (Materials associated with AHPs that are not part of the actual wearing experience – such as wrappers, release films, and applicators – are removed prior to milling.) The method specifies a means by which sufficient sample homogeneity is confirmed through visual assessment and chemical elemental analysis of multiple specimens of milled sample material. Acceptable mass recovery is also affirmed.

Benefits of homogenized milling and extraction include:

- Amenable to trace instrumental analysis. The ratio of body fluid simulant to AHP sample material mass is similar to that used in whole product extraction – that is, generally far in excess of the design intent of the AHP mass such that free simulant is present and can be collected easily after the extraction step for trace analysis (e.g., 1 g specimen per 50 mL simulant). Body fluid simulant recovered in this approach can be concentrated (“dried down”) and/or otherwise further processed to enable lower LOQs in subsequent analytical instrumental analysis.

- Scalable. Specimen mass can be arbitrarily scaled without loss of faithfully representing overall article composition, particularly if more is needed to enable method LOQs. A 1-gram specimen is our standard recommendation, which is more easily deployable than whole-product extraction.

- Assures uniformity. A single sample can be created from multiple nominally identical AHP articles, thereby eliminating concerns about article-to-article variation in the presence of trace chemicals.

- Traceable. Because multiple AHP articles can be milled to create a single, uniform sample material, true retain samples are made possible. This enables unforeseen lab retesting or “round-robin” testing to verify reproducibility of results if needed.

- Flexible. Because representative homogenized AHP material is the endpoint of the milling process, the number of articles needed to achieve a target mass is unimportant. The milling approach, therefore, easily accommodates different-sized AHP articles (e.g., different-sized diapers) and contrasting product forms (e.g., diapers and tampons).

- Creates surface area. The milling process finely divides constituent AHP materials, shortening diffusion lengths required for any trace chemicals present to migrate to the body fluid simulant during the extraction step.

- Uses commercially available apparatus. No custom-built apparatus (e.g., rewet beds to uniformly apply consumer-relevant pressure) is required. Commercially sourced and readily available mills meet the milling success criteria. CWA 18062 has proven to be easy to handle across a range of competent laboratories, is robust (repeatable and reproducible), and reflects consumer-relevant aspects. It is:

- Relevant. Products are tested under circumstances that reflect aspects of typical consumer usage.

- Robust. The method delivers consistent results independent of the operator or the laboratory that is running the test. In effect, the method is repeatable and reproducible within a tolerable level of uncertainty. The method delivers reliable results within the operating parameters of the method (considering variable environmental background levels).

- Deployable. Any laboratory with state-of-the-art analytical equipment and well-trained staff can run the method in a transparent and accessible manner.

CWA 18062 is a good example of a standard analytical method that incorporates critical aspects of consumer relevance, thereby giving rise to results that are more closely related to the consumer experience/risk than harsh organic extraction. While EBRA will always be the correct tool for rigorous affirmation of objective product safety, CWA 18062 is and will continue to be a valuable tool for manufacturers, regulators, retailers, consumer groups, and NGOs to use in discourse where EBRA is out of scope.

References

- Kosemund, K., Schlatter, H., Ochsenhirt, J. L., Krause, E. L., Marsman, D. S., Erasala, G. N., (2009) “Safety evaluation of superabsorbent baby diapers,” Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2008.10.005.

- Krause, E. L., Hattersley, A. M., Abbinante-Nissen, J. M., Gutshall, D., Woeller, K. E., (2023) “Support of adult urinary incontinence products: recommendations to assure safety and regulatory compliance through application of a risk assessment framework,” Frontiers in Reproductive Health, DOI:10.3389/frph.2023.1175627.

- Hochwalt, A. E., Abbinante-Nissen, J. M., Bohman, L. C., Hattersley, A. M., Hu, P., Streicher-Scott, J. L., Teufel, A. G., Woeller, K. E., (2023), “The safety assessment of tampons: illustration of a comprehensive approach for four different products,” Frontiers in Reproductive Health, DOI:10.3389/frph.2023.1167868.

- Dey, S., Purdon, M., Kirsch, T., Helbich, H. M., Kerr, K., Li, L., Zhou, S., (2016), “Exposure Factor considerations for safety evaluation of modern disposable diapers,” Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2016.08.017.

- See https://www.edana.org/how-we-take-action/edana-stewardship-

programme-for-absorbent-hygiene-products - EDANA, the European Nonwovens Industry Association, is a leading global

association and voice of the nonwovens and related industries, see www.edana.org. - Use of International Standard ISO 10993–1, “Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices – Part 1: Evaluation and Testing Within a Risk Management Process;” Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff; Availability, 88 Fed. Reg. 62,091 (Sept. 8, 2023). Available at https://www.fda.gov/media/142959/download.