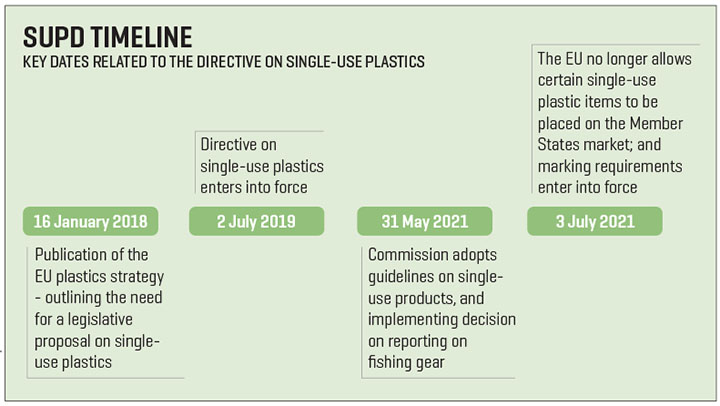

The European Commission’s Single-Use Plastics Directive (SUPD) has been hotly debated since its initial publication in July 2019. While the aim of the legislation is a noble one – minimizing plastic waste in the environment – getting a firm grasp on what is, and what is not, a plastic has proven to be more challenging than some might have expected.

Now, with the latest SUPD guidance published on May 31, The European Commission has provided clarity for the near term, albeit not the sort of clarity some biopolymer producers might have hoped for.

The EC’s clarification on which materials fall under the SUPD, and which do not, was eagerly (nervously?) anticipated, particularly for producers of certain cellulose-based materials, such as viscose and lyocell, and biopolymers, such as PLA (polylactic acid) and PHA (polyhydroxyalkanoates).

As IFJ’s European editor Geoff Fisher explains in his article, “A reprieve for viscose as European Commission publishes new SUPD guidance,” viscose and lyocell were reclassified as natural polymers, relieving them from the requirements of the SUPD. This marked a significant win for producers of regenerated cellulose, as a prior revision of the SUPD seemed to indicate that viscose and lyocell could ultimately be classified as plastic materials (or non-natural polymers).

PLA and PHA were not so lucky, as both materials were not categorized as natural polymers and will fall under the SUPD. On this topic, the EC said:

Based on the REACH Regulation and the related [European Chemicals Agency (ECHA)] Guidance, polymers produced via an industrial fermentation process are not considered natural polymers since polymerization has not taken place in nature. Therefore, polymers resulting from biosynthesis through man-made cultivation and fermentation processes in industrial settings, e.g., polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA), are not considered natural polymers as not being the result of a polymerization process that has taken place in nature. In general, if a polymer is obtained from an industrial process and the same type of polymer happens to exist in nature, the manufactured polymer does not qualify as a natural polymer.

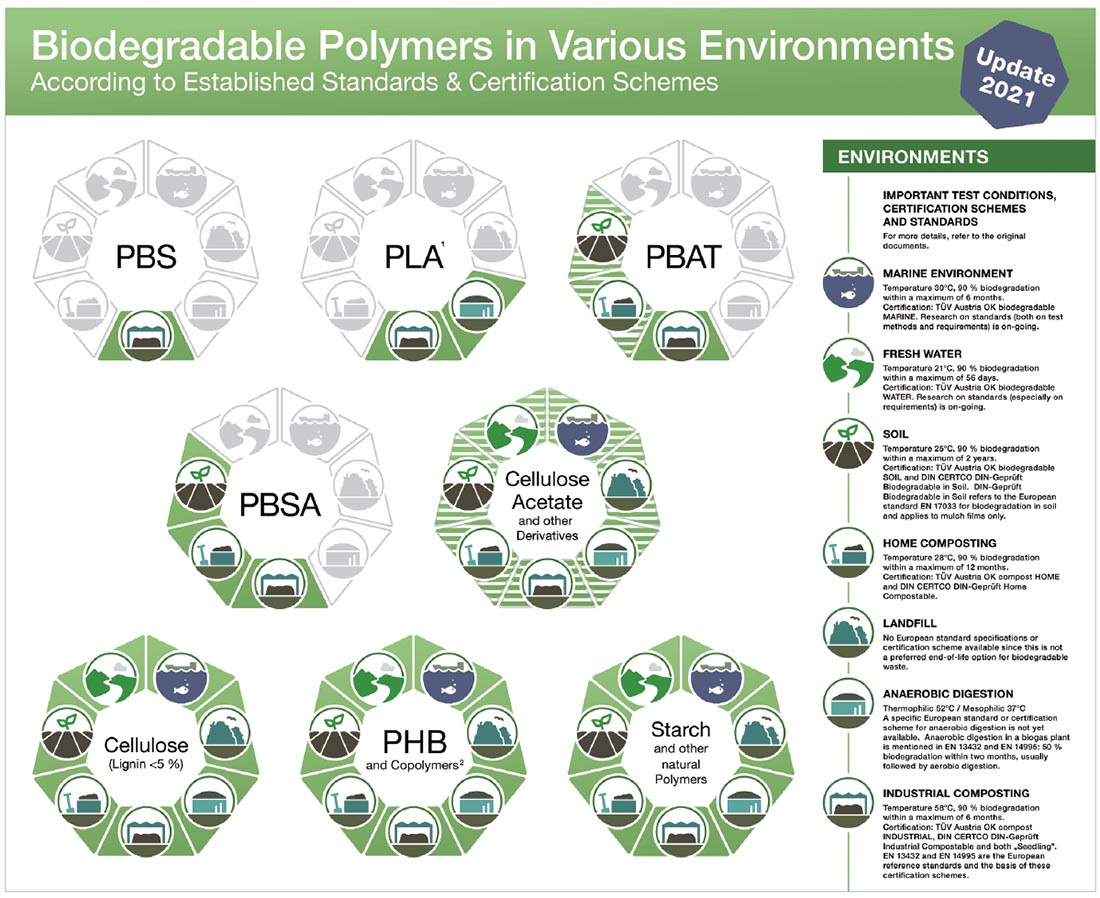

While most believed PLA – which requires industrial composting for biodegradation – would likely be classified as a plastic (or non-natural polymer) regardless of the EC’s latest update, the classification of PHA as a non-natural polymer was a bit of a surprise, as PHA-based materials more readily biodegrade in the natural environment.

In determining its position on PHA, the EC relied heavily on the European Union’s REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals) regulation dating from December 2006. REACH addresses the production and use of chemical substances, and their potential impacts on both human health and the environment. It focuses narrowly on the chemical makeup of materials. Some argue that in using such a specific guideline, certain materials that are, in part, aligned with the ultimate goal of the SUPD are being caught up in the regulation.

“The EU SUPD has declared some very desirable-performing materials to be ‘plastic’ and therefore subject to the remedies of the SUPD, which can be quite severe to the marketability of those materials,” said Dave Rousse, president of INDA, the North America-based association representing the nonwovens industry. “While viscose and lyocell were determined to not be plastics, PHA and PLA were, and these two materials deliver on the real solution of responsibly sourced inputs and responsible end-of-life options. It should be performance that counts, not chemistry.”

As of July 3, EU member states require certain single-use plastic products bear a marking on the packaging or product itself. The marking concerns single-use plastic products such as:

- Sanitary towels (pads), tampons and tampon applicators;

- Wet wipes, i.e. pre-wetted personal care and domestic wipes;

- Tobacco products with filters and filters marketed for use in combination with tobacco products; and

- Cups for beverages.

The directive also requires member states to establish new extended producer responsibility (EPR) schemes for a large number of single-use plastic products and for fishing gear containing plastic. In order to comply with this obligation, member states will need to identify the relevant producers of products and establish financial and/or operational obligations on them to manage the waste stage of the product life cycle.

Regardless of the EC’s classification of biopolymers as plastic, major manufacturers are investing in this area as part of their ESG (environmental/social/governance) initiatives. Kimberly-Clark, for example, recently announced a partnership with RWDC to develop alternatives to traditional plastic in support of its sustainability goals.

While most believed PLA – which requires industrial composting for biodegradation – would likely be classified as a plastic (or non-natural polymer) regardless of the EC’s latest update, the classification of PHA as a non-natural polymer was a bit of a surprise, as PHA-based materials more readily biodegrade in the natural environment.

“We are working jointly with RWDC to develop cost-effective biopolymer solutions, including a new source material made from renewable PHA,” said Liz Metz, vice president of Global Nonwovens at Kimberly-Clark. “RWDC uses plant-based oils to produce its PHA, which can be composted in home and industrial composting facilities. Should products or packaging made with PHA find their way into the environment, they biodegrade in soil, fresh water and marine settings, preventing persistent plastics from accumulating in the environment. RWDC has received internationally recognized biodegradability and compostable certifications for its PHA material from TÜV Austria.”

By 2030, Kimberly-Clark has committed that 75% of the material in its products will be either biodegradable or will be recovered and recycled. This is part of the company’s global ambition to improve the lives of 1 billion people in vulnerable communities around the world – with the smallest environmental footprint.

“When evaluating potential sustainable materials, we take numerous factors into consideration, including degradability, recyclability and carbon impacts. We’re exploring a number of innovative alternatives to traditional fossil fuel-based plastics, including PHA, as we look to create the next generation of sustainable materials without compromising on product performance and quality,” said Metz.

PLA is also seen by many as part of the path to a more sustainable solution to the challenge of plastics in the environment. NatureWorks, manufacturer of PLA-based Ingeo polymers and fibers, has rooted its philosophy in the principles established by the Ellen Macarthur Foundation’s New Plastics Economy, which aims to address the problem by: 1. decoupling from carbon feedstocks; 2. reducing leakage into the natural environment; and 3. establishing economically viable after-use pathways.

NatureWorks’ PLA-based materials are already in wide use and generating significant interest in the marketplace because they are plant-based (cassava, corn starch, sugar cane, etc.), carbon positive and cost-effective biopolymers.

“Interest in our PLA-based solutions is at an all-time high, so the [SUPD] is not impacting our business,” said Robert Green, vice president of Performance Polymers at NatureWorks. “PLA is going to be part of the solution – it’s not going to be the silver bullet – but it’s definitely going to be part of the solution.”

One of the challenges often cited in association with PLA and other materials that require industrial composting is a lack of composting infrastructure.

“Existing infrastructure in most countries is not yet prepared to facilitate the move to responsibly handling the needs of a circular economy and the need for responsible end-of-life treatment of desired materials,” said INDA’s Rousse. “Having a strict definitional approach to the plastics issue does not help. In the U.S., where consideration is now being given to infrastructure spending, issues like industrial composting facilities and recycling facilities need to be addressed. We see a lot of recognition of this need and are hopeful meaningful progress will be made to address this need.”

In Europe, there are directives similar to the SUPD that are focused on composting infrastructure. These directives call for recycling and preparing for reuse of municipal waste (including bio-waste) to be increased by 70% by 2030; phasing out of landfilling for plastics, paper, metals, glass and bio-wastes by 2025; and measures aimed at reducing food waste generation by 30% by 2025.

“Industrial composting is primarily meant for food waste,” said Mariagiovanna Vetere, global public affairs director for NatureWorks. “The only way to deal with large quantities of food waste is with industrial composting. Obviously, industrial composting infrastructure will need to be invested in to meet these goals.”

Italy, for example, is using EPR funds from cleanup taxes levied on manufacturers of compostable plastic products to support the development of composting infrastructure.

With investments of this sort, NatureWorks sees an opportunity for PLA to achieve even more widespread use as a sustainable alternative to traditional plastics in the longer term. As such, Vetere said NatureWorks is collaborating with composting stakeholders to help facilitate infrastructure development. Likewise, it is in communication with the European Commission to ensure PLA and biopolymers in general receive another evaluation within the context of the SUPD, as the directive is planned for review in 2027, with the status and handling of biopolymers likely to receive reconsideration at that time.

“Governments are trying to do the right thing, and we’re trying to do the right thing as well,” said Leah Ford, global marketing and communications manager for NatureWorks. “It’s going to take some time to come to the right solution.”

For the latest information on the European Commission’s Single-Use Plastics Directive, see https://ec.europa.eu/environment/topics/plastics/single-use-plastics_en.

* International Fiber Journal is owned by INDA, Association of the Nonwoven Fabrics Industry (inda.org).