Made in America Must Be More About Manufacturing than Marketing

Politicians like nothing better than a catchy slogan: “Made in America” and “Buy American” certainly fit those criteria, but are these phrases beguilingly simple? The origins can be traced back to the Buy American Act of 1933, when legislation required the federal government to purchase American-made iron, steel and manufactured goods where possible. Under the guidance provided, a product could be described as made in America if it met the requisite minimum 50% of its materials or constituent parts having originated in the United States. More recently, one of the very few things that the Trump and Biden administrations have agreed on is the desirability to move manufacturing back, near-shoring or re-shoring, in addition to encouraging American consumers to purchase American-made products more consciously.

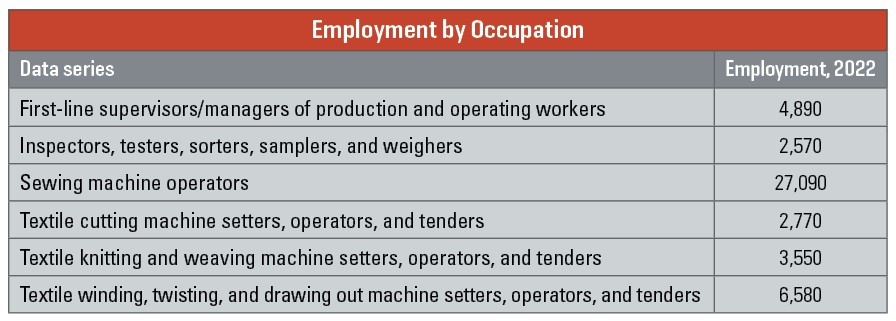

While the U.S. textile industry is in favor of these policies, the counter and temperance arguments ought not be ignored. “Buy American policies actually cost jobs” is an argument made by Adam Posen, President of the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), writing in the Spring 2023 issue of Foreign Policy magazine. The National Council of Textile Organisations (NCTO) meanwhile point to a U.S. textile industry supply chain that employed 538,067 workers in 2022, as well as government estimates that each textile manufacturing job itself supports three further jobs.

The purpose of this article is not to express an opinion on the U.S. policy, but instead to look at some of the proposals emerging from the debate that have the potential to make the textile industry stronger, while generating positive societal impacts that stretch beyond U.S. borders.

In Posen’s claim that “Buy American policies actually cost jobs,” he points to “rules of origin” as increasing product costs thereby making U.S. business less competitive on the international marketplace.

Policy at Play

The U.S. is the third largest exporter of textile-related products in the world with textile and apparel shipments worth $65.8 billion in 2022 according to the National Council of Textile Organizations (NCTO). An impressive figure but might it be higher?

In Posen’s claim that “Buy American policies actually cost jobs,” he points to “rules of origin” as increasing product costs thereby making U.S. business less competitive on the international marketplace. Under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the “yarn-forward” agreement demanded that the majority of textiles and apparel from the yarn stage forward had to be made within the region in order to qualify for duty-free status.

There were some exceptions, which the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) looks to close through the introduction of “chapter rules,” thereby extending the application of rules to sewing threads, narrow elastic bands, pocketing, and coated fabric.

Bill Jackson, interviewed last year in his position as Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Textiles, described the measures as having “strengthened the regional supply chain for textiles and provide new market opportunities for the U.S. textile and apparel sector.” Jackson pointed to the Dominican Republic Central America FTA (CAFTA-DR) trade agreement that under the yarn-forward rules gives apparel made in Central America duty-free access to the U.S. market, providing what he believed to be a “foundation upon which the industry can grow, while at the same time supporting jobs in the U.S. industry, which supplies much of the fibers, yarn and fabric used in apparel production in CAFTA-DR countries.” The U.S. government has been encouraging new investment with CAFTA-DR partners to strengthen the regional supply chain.

Reflecting industry views, Steve Schiffman, president of the Advanced Textiles Association (ATA) comments: “The stance of [United States Industrial and Narrow Fabrics Institute] USINFI is that it needs to continue to be Yarn Forward, and the rules of origin should not be weakened to offer other countries the chance at an end run around the current requirements. USINFI opposes any attempt to weaken the Yarn Forward rule of origin under the CAFTA-DR or any free trade agreement.”

Trade lawyer Lori Wallach, directs the Rethink Trade program at the American Economic Liberties Project, and cautions that “this [Biden] administration has articulated goals like creating good jobs for workers with and without college degrees and strengthening economic resilience, and our trade policy and deals must deliver not damage that.”

Potholes in the Supply Chain

One of President Biden’s first actions when he was appointed to office in 2021 was the signing of two Executive Orders aimed at reducing vulnerabilities in the supply chain. One outcome was the National Strategy for a Resilient Public Health Supply Chain (2021), a roadmap for building and sustaining resilient supply chains for PPE and other essential medical products. The risk of obsolescence makes it too risky for the government to store a high level of inventory in the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS). “I think the roadmap for building and sustaining resilient supply chains for PPE and other essential medical products is a good start and we’ll have to see how it plays out in the future,” believes Steve Schiffman. “USINFI supports legislation such as the [Homeland Procurement Reform] HOPR act which includes medical PPE, uniforms, etc. This is to help government contracts go to small businesses. This is an example of legislation that is part of the building blocks to help strengthen the supply chain.”

The demand for PPE is not consistent and this has already impacted U.S. mask producers with the American Mask Association estimating by September 2021 that as many as ten out of twenty-nine domestic manufacturers had ceased production, with some being forced to file for bankruptcy. There is the potential to put safeguards in place particularly for smaller producers. One possibility would be reservation contracts, whereby the government could exercise an option with suppliers for increased production should the need arise.

“Detailed research has repeatedly shown that policies aimed at maximizing domestic manufacturing employment rather than the development and adoption of new technologies are not only doomed to fail but crowd out the very industrial and trade policies that contribute the most to innovation, national security, and decarbonization,” warns Posen. He argues for the prioritization of technology adoption over technology production. This is an important differentiation, with so much focus on the protection of intellectual property (IP) the risk is of technology obsolescence before an innovation has been properly taken up. The outcome is to starve the next level of innovation that is served by the iterative process of lessons learned and improvements needed that can only be properly seen when a technology is used at scale.

Technology or Training?

The move to a more digitally connected manufacturing environment, such as Industry 4.0, further exacerbates this negative impact. Technology adoption provides the opportunity for a more highly skilled and engaged textile workforce, essential for good employee retention. However, education and training is not the only issue, as experience in Europe shows. Germany has an abundance of training centers from the Textilakademie NRW to the Texoversum at Reutlingen University, yet in 2021 there were 63,000 apprenticeship and training positions that remained unfilled. The pandemic would partly account for this, however one third of these remained unfilled at the end of 2022 in the region of Saxony and Thuringia alone, according to Dr. Uwe Mazura, Director General, Confederation of the German Textile and Fashion Industry. Demographic changes are one reason, according to Dr. Mazura, with more people retiring from the industry than there are young people entering.

While Germany is looking at ways to attract and retain a young workforce, the UK launched a campaign in Spring 2023 to entice recent retirees back to the workforce. An estimated 630,000 people retired in UK between 2019 and 2022 and the British government wants them back at work. In the U.A. Jerome Powell, the Fed Chairman, bemoans 3.5 million people absent from the workplace since the pandemic, with many over 50 years old and, like the UK, often newly retired. In the UK, around 42% of the workforce is aged over 50 with the figure set to rise to 47% by 2030 – the figure in U.S. is thought to be one third of that.

To attract recent retirees, “work will need to offer different incentives – flexibility, purpose and community, for example,” according to Aviva Wittenberg-Cox writing in Forbes magazine earlier this year, pointing to an additional expectation that an employer should offer “a conscious rejection of ageist systems and policies, the continued investment and development of careers for people 50+.”

The People Problem

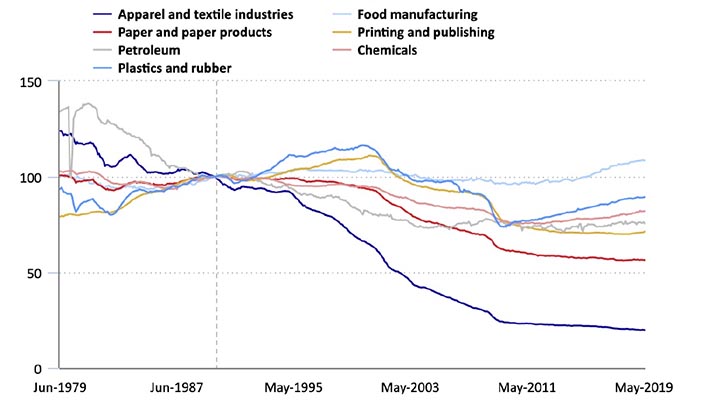

In 2022, most of the apparel sold in America was manufactured in other countries, with the Sourcing Journal putting the figure as high as 97%. The U.S. Bureau of Statistics estimates that 81% of jobs in the industry were lost in the period between 1979-2019 as the industry looked overseas for low-cost manufacturing.

The United States Fashion Industry Association undertakes an annual USFIA Benchmarking Study, with most recent being for 2022. It points to respondents concerns about attracting and retaining employees, moving the issue from one of medium ranking to one of the top five business challenges they face. Companies have indicated an average of six different positions they are looking to hire: supply chain specialists; sourcing specialists; environmental sustainability-related specialists; market analysts; and, trade and custom compliance specialists.

In contrast, the report also found no sign that fashion companies planned to near or re-shore manufacturing, with positions in sewing machine operators and general management their least likely positions to increase. Asia remains the strongest supply source for U.S. fashion, with over 37.5% planning to source for a greater number of suppliers and countries over the next two years. CAFTA-DR is growing in importance for the apparel industry with 60% of respondents planning to increase their sourcing from the region as part of a sourcing diversification strategy.

“Made in America” and “Buy American” are prompts for deeper questioning around benefits and impacts, from economic to social and environmental.