The textile and apparel industry’s linear business model of make, use and dump has been perfected over many decades and ensures that the 80 billion new pieces of clothing now produced each year are worn on average only four times.

It’s an unacceptable status quo many are now trying to change, including The Renewal Workshop (TRW), which has bases in Portland, Oregon, and Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

At the recent virtual BiotexFuture (BTF) Forum co-organized by adidas AG and the Institute of Textiles (ITA), at RWTH Aachen University in Germany, the company’s co-founder Jeff Denby observed that the apparel industry is simply geared towards making and selling more each year.

Unlocking value

“It’s a business model that uses a huge amount of resources on products that are barely used, while largely externalizing the waste problem to other players,” he said. “We are exploring how to unlock more value in what’s already produced by the industry, as a service provider enabling brands to be able to face up to this problem. It’s about decoupling resource use from resource growth.”

TRW has already partnered with brands including The North Face, Coyuchi and Tommy Hilfiger. It collects all of the products deemed waste inside their organizations and also runs a take-back program that the brands can operate through their own websites allowing customers to return products.

“We do all of the sorting, cleaning and repairs at our facilities in Portland and Amsterdam to restore as much of the waste to a like-new condition, and also reconnect the original product data with the item in order to know what it is and enable the second sale of that product,” Denby explained. “Our system then connects to a resale platform that we can establish on any site, for any brand to have their own resale site on the market. Anything that we can’t renew, we manage through upcycling or recycling channels, and we collect a lot of data on product quality.”

The resale market, he added, is currently growing 11 times faster than the retail clothing market.

“Brands are the last to the party and third-party sites are eating their lunch, but there’s a lot to it, so as an external service provider we can add a lot of value. Brands and retailers lack systems to recover value from unsellable inventory. For products that have been produced but cannot be sold, the creative, physical, natural and financial resources invested in them are lost. This leads to massive waste problems with negative environmental impacts and also significant financial losses for brands.

“Compare this to how the car industry, for example, operates. It has known for many years how to take advantage of this resale space, with the car brands selling both their new and used cars under their own umbrellas. In the U.S., there are seven million new cars and 40 million used cars sold annually by the companies who make them.”

Carbon generation

To emphasize the benefits of decoupling resource use from resource growth, Denby cited figures for the carbon footprint of the textile and apparel supply chain. Raw materials production accounts for 11%, fabric production 48%, and garment manufacturing 21%.

“So, 80% of the carbon impact is in the making of new products,” he said. “All of a brand’s retail spaces, distribution centers and offices, and its corporate travel, amount to less than 1% of its carbon footprint. A brand can put solar panels on all of its stores and offices but not make a dent on the issue. It is production that is the problem and that’s where new business models like ours can come in and be effective, if we are ever going to get anywhere near the carbon goals we are hoping to achieve.”

Of all the garments processed by TRW over the past two years, around 50% have been resold with no repair work carried out, and a further 32% resold after repair, with only 18% deemed waste and going to recycling.

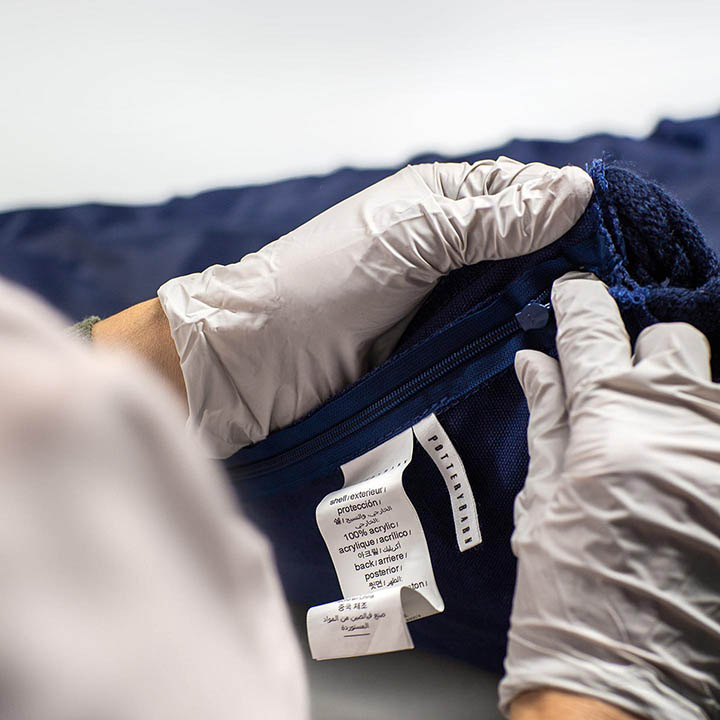

“There’s a lot of value that exists here, but the key to really unlocking it is knowing what it actually is, which is a big challenge inside the circular economy,” Denby said. “All we have is a bunch of codes on a little white tag. However, we’ve figured out a way to connect that into the systems of our brand partners and pull out the data.

“It’s really important that those tags are there so that we can identify what the material is, particularly if the garment is going to need to go to recycling.”

Digital passports

Denby mentioned the critical work of New York-based Eon in this respect.

Eon is partnering with Microsoft and a number of retail fashion brands to initially bring 400 million products online by 2025, through a collaboration that introduces an industry-wide digital foundation for a connected and circular economy across fashion, apparel and retail.

“I’d like to see all public companies introducing a production reduction metric in their reports, but at the moment we’re not at the stage of being able to show revenues increasing and production decreasing. This should be the aim.”

“The digital passports project Eon is working on will really make this ecosystem start to work, so that as garments move through the circular system it’s possible to work out exactly what they are, how much they were priced at originally, their features and benefits, and their construction,” Denby said. “At the moment we are sorting by material type so we know what recycler a garment can go to, but the data on current tags is not great. A garment might be labelled as 100% polyester, for example, but still have a coating on it which means that a specific recycler cannot handle it. These are the kind of details we need to start gathering.”

TRW has learned a great deal since its formation in 2016, and now runs workshops for brands on circular design.

New Balance Renewed

This August, TRW announced its latest partnership with New Balance, to create the New Balance Renewed platform giving the brand’s apparel a second life.

“New Balance is constantly learning and evolving our approach to create quality, long-lasting design,” said John Stokes, director of global sustainability for New Balance. “In April 2021, TRW led a workshop during our design week, to help educate designers on how to intentionally design future apparel for repairability and garment recycling. Together with TRW, we’re keeping apparel in use for longer and learning how to design for circular.”

Incentivize innovation

Asked what the biggest inhibitor to decoupling resource use from resource growth is, Denby observed that a couple of things were inherent to the brands.

“The expectation is that innovation will be margin positive on the first day, but to engage in business model change takes both time and investment,” he said. “The reason brands can achieve positive 70-80% growth is down to an enormous infrastructure, mostly in Asia, that is designed just to serve.

“As we start to change it, it’s fundamental to understand the scale we are building towards, and you don’t get to that growth on the day you launch. Many brands are also public and have to report to shareholders every three months, which is not an incentive to innovate. A lot of things are making this change difficult, but it needs top-down, CEO-level commitment to allow for employees to be incentivized and encouraged to try and take on risks. I’d like to see all public companies introducing a production reduction metric in their reports, but at the moment we’re not at the stage of being able to show revenues increasing and production decreasing. This should be the aim.”