Interview with Report Author Brett Mathews

The April launch of a new report “Textile Recycling: State of Play,” was directed not just at the textile industry but at potential investors. I spoke with report author Brett Mathews, textile and apparel industry writer, influencer and disruptor, also publisher and editor of Apparel Insider magazine that has long focused on sustainability. Never one to hold back on saying it how he sees it, I began by asking why a report on just one aspect of circularity, and why recycling?

Marie O’Mahony: First Brett, congratulations on a really insightful report! In Apparel Insider you write about all aspects of circularity, so why did you decide to focus on recycling for this report?

Brett Mathews: We chose recycling because this is the issue we are asked about the most. In the past few years various consultants have approached us to ask for our thoughts on textile recycling, prospects for this segment etc. So, the initial plan was to produce a kind of investor guide to textile recycling so we could point them to this publication. Then as we looked into this, it became harder to produce just a small briefing. We wanted to produce something coherent which would give ALL industry stakeholders an idea about where we are right now with recycling, with a focus on novel recycling technologies.

MO: The main emphasis of the report is on chemical rather than mechanical recycling processes driven by industry stakeholder interest. You describe how less than 1% of recycled clothing is being recycled using chemical processes and point to Spinnova’s mechanical recycling process as clean and environmentally benign. Do you agree with stakeholder emphasis on chemical recycling?

BM: I think there is room for both chemical and mechanical. We focused on chemical as that seems to be where much of the interest is in terms of investment. The theory goes that chemical recycling offers the potential to recycle some clothing which mechanical recycling cannot. But, of course, there are caveats to that which we explore in the report. It’s worth noting that mechanical recycling is by far the most popular and it’s been happening for decades, very successfully. India and Pakistan are huge secondary markets for mechanical textile recycling and it’s a really important part of the value chain. So, I think that it would be a mistake to get carried away with the chemical textile recycling being the ‘be all and end all,’ it’s not, and there is still a huge part to play for traditional mechanical recycling. There are some big players in this area. Recover in Bangladesh is taking off-cuts from the production process and mechanically recycling it. They are working with brands such as Tillys in the U.S., on their sustainable RSQ capsule collection that contains a minimum of 20% low-impact recycled cotton fiber according to Recover. The benefit of chemical recycling is that it offers a way of recycling more difficult fibers such as the blends so that it is a more ambitious way of doing things.

MO: Some fiber and yarn spinners have spoken of the technical challenges in using recycled content, such as short fibers, nep content and the fineness that can be achieved. Do you see evidence of the two industries working together to overcome this?

BM: Not in any major way. Fashion has talked for years about designing for circularity. But apart from a few pilots and one-off initiatives I haven’t seen much evidence of this. Plus, the market is now being flooded with ultra-cheap clothing from the likes of Shein, Boohoo which is mainly polyester and more difficult to recycle than ever. On the quality of recycled fibers, people that I have spoken with have said that they are actually pretty good and it’s quite difficult to tell the difference between these and virgin fibers. We’ve seen C&A designing fully circular denim jeans, but this is going back three or four years and I’m not sure there has been much follow up on that. There’s quite a few that have worked with the Ellen Mac-Arthur Foundation that have put out guidelines on circularity, including some specifically relating to jeans. A few brands have done small pilot productions but it’s all a bit ad hoc and no one has really scaled this work which perhaps tells its own story.

MO: Elastane you cite as a big issue of course, do you see more sustainable stretch fibers such as the Roica Eco-Smart range or Cotton Inc.’s stretchable cotton as offering a good alternative?

BM: Potentially yes. Without checking, I am guessing these fibers will come at a premium over conventional elastane. This being the case, they will remain niche. Fashion brands are ultra-sensitive on price, especially in the fast fashion space. Luxury brands might be more willing to absorb this premium as their margins are greater. In 2019, Cotton Inc. developed a 100% cotton elasticated fabric called Natural Stretch, that uses a special mechanical manufacturing process to provide stretch. According to the company’s website there are only a small number of licensed suppliers, all bar one in Asia and none in North America. I’m not sure how successful it has been, I don’t know of any brands using it, so it looks like it is not getting any significant market traction.

MO: Declining qualities of feedstock is proving challenging for chemical recyclers. Fast fashion is not going away any time soon so are you seeing any innovative work-around for the quality problem?

BM: Not really. As mentioned previously, we have seen pilots and one-off lines but in the main the business model remains the same. There is a real disconnect on this issue in terms of what brands say on circularity and recycling and the clothing they produce. It is hard to over emphasize also the impact of brands such as Shein and Temu. They are a huge threat to the legacy of fast fashion players such as H&M, Primark etc. There is a genuine danger these new ultra-fast fashion brands will lead the industry in a fresh race to the bottom, including on quality issue.

MO: You have mentioned the Ellen Mac-Arthur Foundation a few times, and I get the sense that you are seeing a lot of exciting initiatives coming through the foundation but not actually scaling up.

BM: A lot of what the foundation is suggesting or asking brands to do is idealistic, it would cost more money in theory to do. So, they have come up with these design guidelines and various other initiatives, but it’s all a little bit pie in the sky. A lot of brands have signed up and there is a lot of funding, but in terms of practical impacts on the ground I can’t see what’s happened on the ground, so I do wonder what they are actually achieving for the industry. My question to them is that having been operational for more than ten years, can they tell us something tangible that they have done, apart from a catalogue of reports, to make the industry better and more circular?

MO: When you interviewed Afry about the biggest problem to scaling chemical recycling, they pointed to five key challenges. Can you tell us what these are and whether you agree with their analysis?

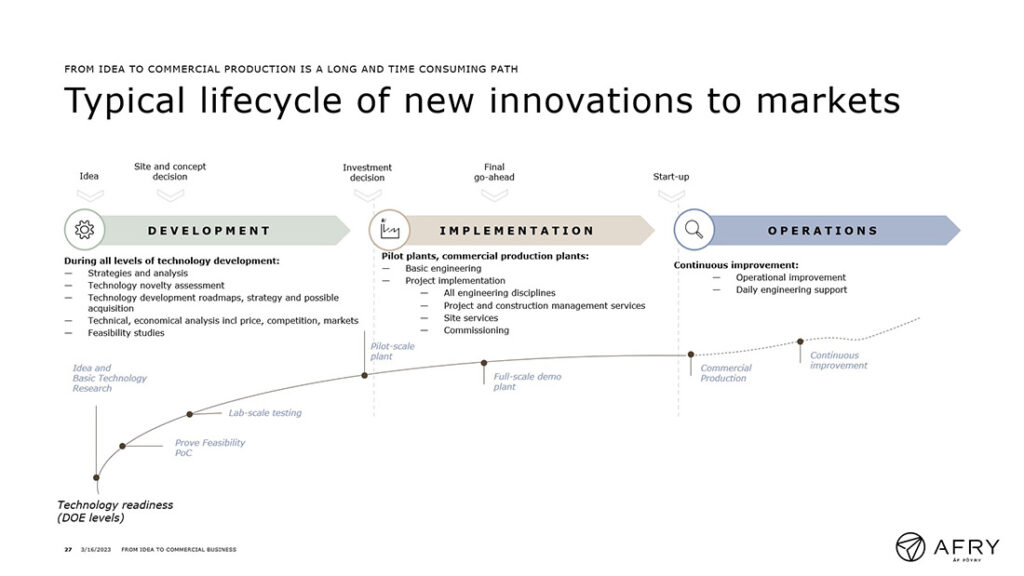

BM: These challenges are technical, regulatory, financial, market pull and supply chain management/logistics. I pretty much agree with all of these! What has to be remembered is that these five challenges have to come together all at once. Not all the technologies are commercialization-ready yet, and while that is happening all the funding streams have to be kept in place and it’s going to be several years before they make any money, making it a nervy thing. Afry is pretty impressive, they take pilot ideas and help them to scale. They were very open about the financial side and what became clear is the huge amount of money that is needed to take projects from a pilot phase to full commercialization – we are talking tens of millions of Euros or dollars. Who is going to fund this? It needs someone with deep pockets really.

MO: Textile collection and sorting for recycling is seen as a significant bottleneck, how is this being done at present, and do you see a role for technologies such as smart labelling?

BM: Sorting is carried out in various ways depending on the location. Often local authorities are involved and these work in unison with charities and private sector partners such as Bank & Vogue and Value Village. Bank & Vogue do some brilliant work, and they are front leaders in how this kind of work can be done. Some countries are more progressive than others on this, however, expect the EU countries to take a lead given the ambitions of the EU Textile Strategy.

I’m not so sure about smart labeling. Like sorting technology, it has been talked about for years but there has been limited progress. Why is this? Is it because of cost (it usually is)? Even in Germany, where wages are among the highest in Europe, they are still doing most sorting by hand as using technology solutions is prohibitively expensive.

It is probably worth noting that sorting technologies are not cutting edge. The technology is not ultra-sophisticated. So, given that sorting has been a requirement for used clothing for decades, why has no major recycling adopted it at scale prior to now? The RFID technology has been around for the best part of a decade and if it’s been around for so long why is it not being used more widely? I’m guessing it comes down to cost.

MO: The focus of your report is the apparel industry, do you see progress being made by the mainstream fashion industry in designing for recycling?

BM: Not to any significant, coordinated degree. The industry is fragmented on this issue, with brands all doing their own thing, putting out occasional lines based on the Ellan MacArthur circularity principles, for instance.

The problem brands face is they are trying to balance competing in an intense price war, on the one hand, with becoming more sustainable on the other. Something has to give at some point. Better made clothing which is more easily recycled costs more and it would be a brave brand that fully committed to this route in the current environment.

It’s a bit like talk of slow fashion and degrowth. Which brand would dare to make the first move on this? And what would shareholders think?

MO: In the UK only 23% of clothing and textiles were collected for reuse or recycling, in the U.S. it is 14% but France is managing to achieve 61%. What is needed here, is it about political will and regulations, or is it about finding a business model that shows profit?

BM: Probably a bit of both. France has led the way on this. It was the first country in Europe to bring in Extended Producer Responsibility laws for textiles and there has certainly been a lot of political will there on environmental issues.

I also get the feeling young consumers in countries such as France and also Germany are more sustainably minded than, say, the U.S. and UK.

Of course, the business model has to show profit. In the UK, I know recyclers have faced huge financial challenges in recent years, with the price of used clothing having sunk to new lows. Much of this comes back to fast fashion, and too much of it flooding the market.

MO: Extended Producer Responsibility (EPRs) for textiles have been adopted by a small number of countries fairly recently. Are you seeing any results yet on how they are getting on particularly around the issue of clothing returns, identifying where the EPR lies and enforcing it?

BM: I think it is still early days on this. Much depends on what the levy is set at for EPR. I understand it is pretty low in France, too low to make much of a difference many believe. But it is a start.

Australia has just introduced a kind of voluntary EPR for clothing. This will become mandatory next year if not enough brands sign up. But again, many think the levy is too low. I think it is around 4 percent that is applied to the manufacturer. I’m not sure how enforceable this is given the complex global nature of the supply chains. Reshoring would make this a lot easier to enforce.

MO: In Part V of the report you offer guidance and recommendations first for Investors, then for fashion brands. Most of the investors mentioned in the report have been fashion brands, what other types of investors do you see entering this space?

BM: Great question. We seem to have seen a growth in the number of investment funds with ‘climate’ or ‘green’ in their name. The talk is that fund managers will increasingly have a focus on sustainable investments moving forwards and, to this end, one could argue that novel textile recycling is a good fit.

But any fund manager will want to see a profit or evidence of a potential profit. They won’t just back these technologies because it seems like the right thing to do. Although we don’t say it directly in the report, some of the solutions would appear to be a better bet than others as things stand. Also bear in mind a hard-nosed investor will ask tough questions and want clear projections on growth, profit, etc. They will want to look right under the bonnet. Other potential investors include philanthropic foundations. Also, might some public sector bodies such as local authorities look to establish public-private partnerships with some of these recyclers? I would not rule this out.

MO: You said at the beginning of this interview that the report was prompted by a desire to reach investment fund managers. Are you seeing any invest at present, also do you see any single advance that would lift the barrier to investment?

BM: Investors I see as those with green funds, ESG investors and those that have ‘climate’ in the name, but they would need to see a return on their investment. To give the HIGG Index as an example. Eighteen months ago, they got $50 million investment, and I guess the difference with the HIGG Index is that it is an existing business model that is known to be working and bringing in lots of revenue and even for them it’s not easy to get this kind of investment. So, I would guess these new technologies are chasing this kind of money but it will be more challenging for them to get this kind of investment because a lot of them are not viable yet. Much of what we are seeing is something very new and it could take years for these companies to get up to scale and that is a challenge. Where you see lots of garments being produced already that makes a difference. If I was an investor I would want to see some clothing that they have made already, otherwise it is just on paper and theoretical. However, companies like Renewcell have tweaked an existing technology so they are getting up and running and I could see them becoming profitable in the next two to three years.

MO: Most of the innovations mentioned in the report come from Europe and North America, can you suggest why this might be and do you see any signs of change ahead?

BM: This is arguably because these are two huge markets for clothing. And the media in these parts of the world has been very loud and vocal on sustainability issues and awareness raising. In terms of this changing, I anticipate some big developments from China. There are dozens of papers on the internet around textile recycling research by Chinese universities. They are a real dark horse here. When China commits to something in business, there tends to be no half measures and if Chinese solutions regarding textile recycling were to be developed they would likely get government funding.

MO: Final question. What would be the one thing that you like the fiber and yarn industry reader to take away from your report?

BM: I would hope the report is a useful guide to the current state of play in this segment, just as the title says. We tried to make it practical and easy to read and offer some genuine insight based on many hours of research and conversations.

“Textile Recycling: State of Play” (2023) is published by Apparel Insider priced £595 (760) and available from https://apparelinsider.com/briefing/textile-recycling-state-of-play/.